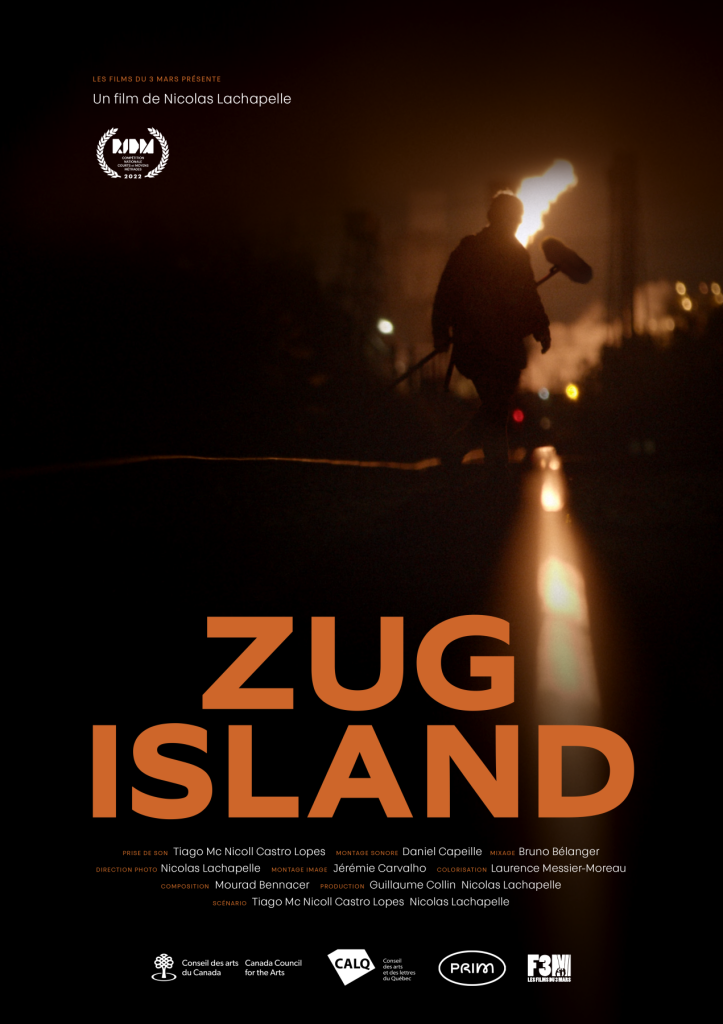

Filmmaker Nicholas Lachapelle’s documentary film ZUG ISLAND, presented on T-Port via our partners at Les Films du 3 Mars, focusses on a mysterious hum heard around an area of Michigan. What the filmmakers found was an abandoned neighbourhood devastated by decades of industrial rollout. We caught up with the director to talk about how he convinced locals to share, and combining his love of audio and cinema documentaries to great effect.

Tell us about yourself:

After completing my studies in filmmaking in Montreal, I left for the North Shore of Quebec, a remote region of Quebec. There, while being a journalist for the Canadian Broadcast Corporation, I began working on my first visual and audio documentaries. My work, whether they document the youth in a northern indigenous community or the daily life of people in Detroit, always explores the physical and metaphysical relationship between people and the landscape they inhabit.

While working on the film, where did you draw your inspiration from?

In the early stage of my documentarist life, I’ve been greatly inspired by the first practitioners of Cinéma Direct in Québec such as Pierre Perrault, Michel Brault, Bernard Gosselin, Gilles Groulx and Arthur Lamothe. Lately though, my movies have been influenced by the documentary techniques of the Sensory Ethnographic Lab and movies at the intersection of ethnographic observational cinema and more creative objects such as Extinção by Salomé Lamas, Space dog by Elsa Kremser and Levin Peter or Aquarela by Victor Kossakovsky.

Next to filmmaking, what do you consider as your passions in life?

I like sound creation. A few years ago, I set out to do a small documentary with only a microphone in hand. The project, which was on women taking part in a demolition derby competition, allowed me to discover the freedom and the creative potential of radio documentary and I’ve been keeping at it since then. I’ve explored several different realities through this and intend on keeping doing it for as long as I can.

How does this influence your filmmaking?

Right now, I develop sound and cinematic projects in parallel. I like to think of these two mediums as complementary rather than two different things. My filmmaking experiences nourish my sound practice and vice-versa. Mainly, my interest in sound has led me to be more aware of the incredible storytelling tool that the sound is. Since this discovery, I’ve spent more and more time thinking and working on the sound of my movies. I’ve even begun to shoot some of my movies only with a microphone, adding images only later on.

How did you first start working on this film? What was the process like and what first sparked the idea to make this film?

It’s a fascination for the Windsor Hum, a mysterious sound bothering people at night, that got me involved with this story. I was already shooting a movie in Detroit on a community of squatters when my music composer told me to look up this story. On a night off, my sound guy and I went to chug beer in front of Zug Island, the presumed source of the Windsor Hum. The flames of the island entranced both of us and kept burning in our head long after we were gone.

Tell us a bit about your film and the filmmaking process – what were your main insights?

We set out to spend a whole month shooting only at night – when the Windsor Hum is usually heard – in Delray for this movie. I hoped that staying that long in the neighbourhood would allow us to be influenced by the mood of the place, to be possessed by it in a way. This is also why I decided to bring along the movie’s editor. While I shot at night, he would edit in the day time. We would meet each night before I went out to discuss what was shot the previous night and what would be on the shot list for the next bit. This process was hard for the entire crew, but allowed us to really “find” the movie on location.

What were the biggest challenges you encountered during making your film?

The people that live in Delray, the neighbourhood in which we wanted to shoot, are often poor, isolated and mistrustful of intruders such as ourselves. There was no way to reach them before the shoot, so we set out to spend as much time as possible there to be able to meet them and convince them to let us in on their life. We had to use patience and be super transparent about our goals. This process involved canvassing the whole neighbourhood for several days and spending a lot of time drinking and smoking with them. That’s only when people began to see that we allowed ourselves to be vulnerable in their presence that they began to trust us.

How was it to collaborate with your cast and crew? Have you formed any particular meaningful connection from someone from the crew you would like to share?

I’ve heard first of the Windsor Hum and Zug Island while I was already shooting a movie with Tiago McNicoll Castro Lopes, a fantastic sound recordist. Both of us got hooked by the story together and dreamt of doing the movie together as well. We co-wrote the early version of the movie and throughout the whole shooting process, I sought his insights. This close collaboration with the other half of my shooting duo proved to be fantastic and reinforced my love for documentaries and small crew. I believe that documentary filmmaking allows each crew member to be involved in the process in a more meaningful way than on a fiction set. The sum of all these sensibilities is for me an obvious plus.

Tell us about the sound choices in your film – what type of score did you use and why?

I’ve been working with the same music composer for my entire career. Mourad Bennacer is always attentive about the vision I sought in each movie and he tends to incorporate as much as possible the sound recorded on location in his scores. This way of working definitely gives a unique texture to each of my movies.

Tell us about the visual choices in your film. What were your main goals and techniques in creating the visual style of your film?

I wanted to show the hell in which the people from Delray are forced to live. In that light, the visuals influences ranged from horror flicks, Stalker from Tarkovsky, Field Niggas by Khalik Allah, Europa by Lars Von Trier. I also used references going from the film noir era all the way to the modern neon-noir filmmakers. In that weird way, films from filmmakers such as Michael Mann, Carol Reed and even David Lynch were also part of my influences.

What would you like people to take away from your film?

Even though the movie isn’t too obviously environmentalist, my concern for what the human kind is doing to the earth is really what fuelled my willingness to do this movie. Over the years, I’ve also grown more and more angry at the climate injustices that we inflict upon the less fortunate. To me, the situation in Delray is a clear example of such injustice and I hope people will be touched by the very inhumane conditions in which the people from this area are forced to live.

What’s next?

I am currently developing a documentary about the meteoric passage of a punk in the small and isolated fishing village of Natashquan in the 1980’s. I am also working on an audio documentary about Indigenous caribou hunters on a hunting expedition in Labrador as well as on a sound recording of northern lights in Churchill Manitoba.

If you are a film industry professional and would like access to the catalogue and more, find out here how to sign up.

Filmmaker? Upload your short film to T-Port or sign up for our newsletter to get regular updates on the current trends and exciting innovations in the short film universe.