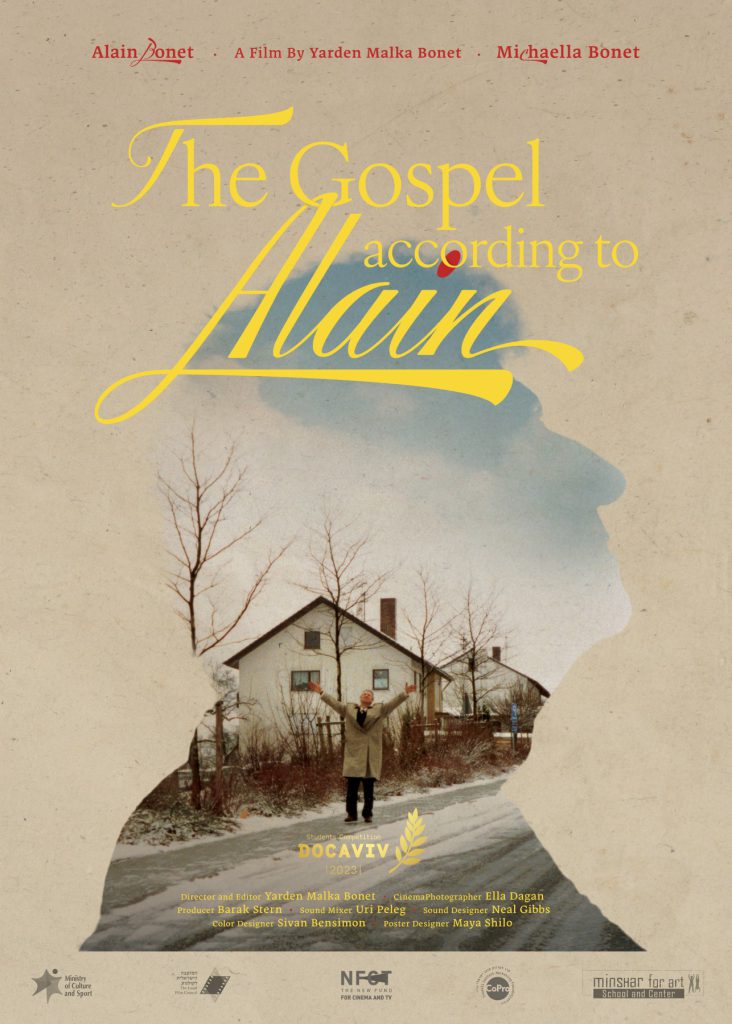

For her documentary THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ALAIN, director Yarden Malka Bonet took on the deeply personal subject of her grandfather, a man who returned to the family after a long absence spent in religious service in Germany.

For her documentary THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ALAIN, director Yarden Malka Bonet took on the deeply personal subject of her grandfather, a man who returned to the family after a long absence spent in religious service in Germany.

In this interview we find out what it felt for the filmmaker, whose work appears on T-Port courtesy of our partners at Minshar School of Art, to be both subject and filmmaker, what she learned about forgiveness and humanity, and what’s next.

Hi Yarden! Tell us about yourself

I’m an Israeli-Swiss filmmaker, 27 years old, based in Tel Aviv. A graduate of the film department at Minshar College for Art.

I started editing when I was 12 years old, and after serving two years as a main video editor in the Israeli intelligence film unit, I continued working as an offline editor and assistant editor for an Israeli TV documentary and reality series. Today I’m a freelance editor.

I am currently working on my next project, a film about a known French artist, who is also my relative. The film contains art, philosophy and revolves around the artist’s community in France in the mid-1900’s.

While working on the film, where did you draw your inspiration from?

My library includes a variety of genres. Among them are poetry, mythology, short stories, film-making and photography books. I find myself sitting in front of the library, waiting for one of the books to catch my attention. Then I randomly open a page, always finding inspiration.

Can you tell us about your first encounter with cinema – do you recall your first memory from watching a film?

The truth is I don’t have one encounter with the cinema. Already from my childhood there are videos where I can be heard, with my high-pitch voice, asking for the camera. After one sharp move and fast cut I’m seen interviewing everyone asking them about their vacation and investigating who’s late for breakfast.

Since I remember myself, my way of communication with the outside world was through documentation.

Next to filmmaking, what do you consider as your passions in life?

This is a question that I make sure to ask myself once in a while, because I’ve never done anything other than film-making. I like to think that the cinema is built from different sources of creators that are united into the platform. To fully understand why I am attracted to what I’m doing, I imagine myself in a desert or on a deserted island, without my camera and the AVID. I would probably draw, maybe use flowers or sculpt in the mud, no doubt using the substances around me. My passion sums up by trying to express my observation towards the world, presenting that complexity that sometimes is impossible to explain with words.

Do these passions influence your filmmaking, are there any connections?

For sure! A few years ago there was a lecture by Nelly Quettier, the editor of “Holy Motors”. At the end she was asked if she has any advice for young editors. She said, “Don’t be scared to crop”, and talked about the materials in the editing program as physical substances that need to be processed and not taken for granted.

As a young editor, this statement opened my eyes. I always remind myself that every raw material has its own elasticity. Breaking and reforming it again and again until the shape is designed into the creation.

How did you first start working on this film? What was the process like and what first sparked the ideas?

When my grandfather returned to the family, I was exposed to his beliefs, which have become an inseparable part of who he is for me. It’s common for me to hear him talk about an entity from the Sirius star system and for him to tell me to “connect to my inner spirit” each time I tell him I have technical computer problems.

My rebellious teenage era was mostly a rage about religion. I refused to celebrate Jewish holidays or to attend bible classes because I didn’t want to learn in the ‘Yeshiva’. In the army I became a bit calmer, but it was also the phase I felt the most disconnected from myself, because if I didn’t belong here, I didn’t know where I did belong.

The only way I was courageous enough to find out was through film. I decided that after the army I would study film-making and create a film about my grandfather, Alain, a person that also doesn’t belong here or there, but finds something strong enough to dare him to leave. (Luckily I also found out what’s important enough to dare to come back).

Tell us a bit about your film and the filmmaking process – what were your main insights?

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ALAIN gently reveals the fragile relations between family and beliefs. In the film I ask Alain about him leaving the family for a spiritual life in Germany for over a decade. By following what were his beliefs, the loneliness from the distance is revealed, aside from the pain from the abandonment. What is strong enough to bring a person back home?

The most important thing I have learned about documenting is that the movie sheds from itself what it finds unnecessary. It’s scary, sometimes even paralysing, but that’s where the magic happens. Just listen, and the movie already speaks for itself. When it happened I found myself amazed by the intensity of it. Sometimes, I only found it through the editing process.

What were the biggest challenges you encountered during making your film?

The thing I found the most challenging by making a personal film was the unequal relations between the character and the director, in this case, my grandfather and I. I was occupied with my fears to hurt my family and disappoint Alain. Sometimes I wanted him to just be a grandfather, and me, only a granddaughter.

A specifically difficult moment was seeing him cry, not knowing if I should stay as the director or the granddaughter. I didn’t want the shooting day to end like this, I didn’t want Alain to feel like I used his vulnerability for my movie. I told him, let’s shoot something fun! He told me about a field abundant with huge, red flowers next to the Kibbutz, so we went and it became my favourite scene.

How was it to collaborate with your cast and crew?

I knew my choice for building the crew would be by intuition, because it was important for me to keep the authenticity of my grandparents. As a team we understood we are entering their private world. Even if a schedule was planned, matching ourselves to them was our first priority.

In front of my grandparents I introduced the crew as “my friends from college that came to help”. When we called for a team meeting, we said, “Let’s take a break”. After every shooting day we slept together at the Kibbutz and it brought us closer as a team.

In the evenings, besides the card unloading and charging batteries, we also sat for beer. They were there for me not one week, not three months, but a whole year!

Tell us about the sound choices in your film – what type of score did you use and why?

From the first moment the soundtrack that guided me was Alan humming a melody, because that’s what he always does. In an interview he told me “I like to sing, I sing without words, these are the things that come deep from the heart.”

I thought I would also design a soundtrack from his melodies to accompany the film, but as the time passed in the editing room, the film shed that too.

What would you like people to take away from your film?

A wound eventually heals. Because the pain of abandonment is so strong, sometimes the only thing you can do is to forgive yourself. Forgiving that it hurts, forgiving that there’s nothing else to do besides being that person that waits until the other is ready to return. Life is complex and sometimes it’s just what you do in families.

What are your plans and dreams for the future?

I want to make a living from a piece of art that echoes to the world, transferring what cannot be explained with words, what can only be transferred through the cinema screen.

At the moment I am learning French in the French institute in Tel Aviv. In the upcoming year I want to find my place on the line between Israel, Switzerland, and France, hoping to find the support for my next documentary movie there. As an editor, I hope I can find my niche in creative documentary editing.

If you are a film industry professional and would like access to the catalogue and more, find out here how to sign up.

Filmmaker? Upload your short film to T-Port or sign up for our newsletter to get regular updates on the current trends and exciting innovations in the short film universe.